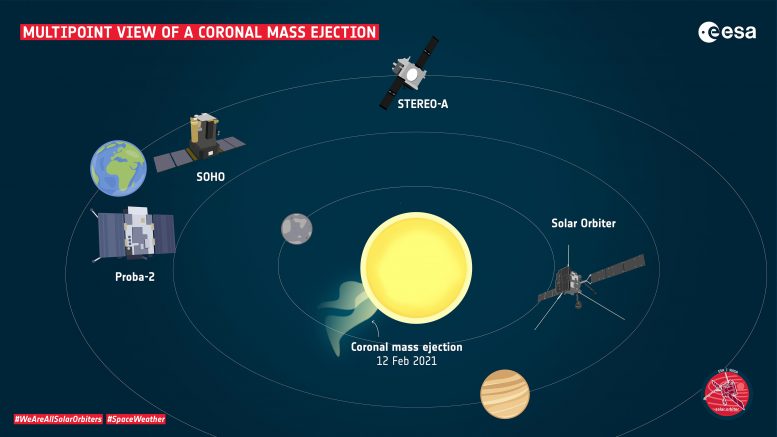

Combining imagery from three of Solar Orbiter's remote sensing instruments - the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI), the Metis coronagraph, and Solar Orbiter's Heliospheric Imager (SoloHI) - provides both close-up and wide views of the evolution of a coronal mass ejection (CME) on February 12-13, 2021. CMEs are eruptions of particles from the solar atmosphere that blast out into the Solar System.

- First Solar Orbiter movies showing coronal mass ejections (CMEs)

- A pair of CMEs were detected by multiple instruments during February's close flyby of the Sun

- CMEs are eruptions of particles from the solar atmosphere that blast out into the Solar System and have the potential to trigger space weather at Earth

- Solar Orbiter will begin its main science mission in November this year

- Solar Orbiter is a space mission of international collaboration between ESA and NASA

Solar Orbiter's Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) captured this coronal mass ejection emanating from the Sun on February 12, 2021. At the time, Solar Orbiter was viewing the far side of the Sun, and the eruption is seen towards the left at about -30º latitude (from Earth, it would have appeared towards the right).

Cruise phase checkouts

Solar Orbiter launched on February 10, 2020, and is currently in the cruise phase ahead of the main science mission, which begins November this year. While the four in situ instruments have been on for much of the time since launch, collecting science data on the space environment in the vicinity of the spacecraft, the operation of the six remote sensing instruments during cruise phase is focused primarily on instrument calibration, and they are only active during dedicated checkout windows and specific campaigns.

A close perihelion pass of the Sun on February 10, 2021, which took the spacecraft within half the distance between Earth and the Sun, was one such opportunity for the teams to carry out dedicated observations, checking instrument settings and so on, in order to best prepare for the upcoming science phase. In full science mode, the remote sensing and in situ instruments will routinely make joint observations together.

ESA's Proba-2 (left) captured the origin of two coronal mass ejections on February 12, 2021. The first is seen at around 10:30 UT at 45º longitude and spanning 0 to -40º latitude, and the second at around 13:20 UT at 75º longitude, -30º latitude. They are seen as dark filaments that rise and cross the limb of the Sun before leaping out into space, as seen farther away by the ESA/NASA Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO)'s LASCO C2 (middle) and C3 (right) coronagraphs.

At the same time as the close solar pass, the spacecraft was 'behind' the Sun as viewed from Earth, resulting in very low data transfer rates. The data from the close flyby have therefore taken a long time to be completely downloaded and are still being analyzed.

Solar Orbiter's Metis coronagraph captured these movies of a coronal mass ejection emanating from the Sun on February 12, 2021. The coronagraph blocks out the dazzling light from the solar surface, allowing the fainter outer atmosphere of the Sun, the corona, to be seen. Metis is the first coronagraph that allows CMEs to be seen in the corona in both visible light scattering by free electrons (left) and UV emission from neutral hydrogen atoms (right).

Chance observations

By happy coincidence, three of Solar Orbiter's remote sensing instruments captured a pair of coronal mass ejections in the days after closest approach. The Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI), the Heliospheric Imager (SoloHI) and the Metis coronagraph captured different aspects of two CMEs that erupted over the course of the day.

Solar Orbiter's Heliospheric Imager (SoloHI) captured this coronal mass ejection emanating from the Sun on February 12, 2021.

The CMEs were also seen by ESA's Proba-2 and the ESA/NASA Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) from the 'front' side of the Sun, while NASA's STEREO-A, located away from the Sun-Earth line, also caught a glimpse, together providing a global view of the events.

Solar Orbiter's Metis coronagraph captured these movies of a coronal mass ejection emanating from the Sun on 12 February 2021. The coronagraph blocks out the dazzling light from the solar surface, allowing the fainter outer atmosphere of the Sun, the corona, to be seen. This is a 'running difference' movie generated from the images seen here, by subtracting from each image the preceding one, a technique used to better emphasize moving features.

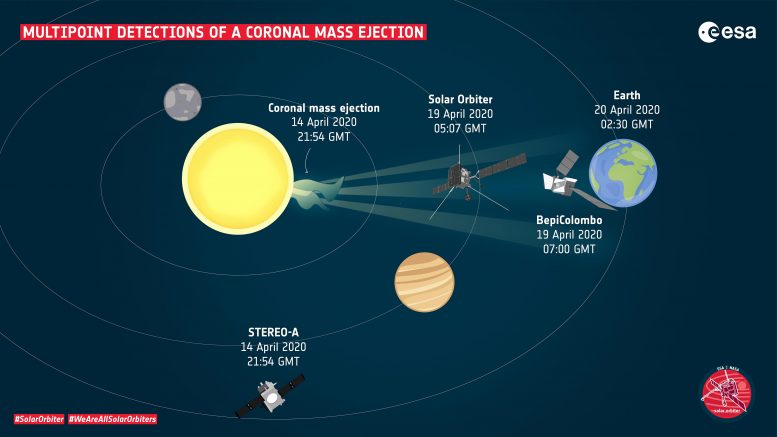

For Solar Orbiter's SoloHI, this was the first coronal mass ejection seen by the instrument; Metis previously detected one on January 17, and EUI detected one in November last year, while the spacecraft's in situ detectors bagged their first CME soon after launch in April 2020. Many of the in situ instruments also detected particle activity around the February 2021 CMEs; the data are being analyzed and will be presented at a later date.

For SoloHI the CME sighting was particularly serendipitous, captured during 'bonus' telemetry time. Upgrades in Earth-based antennas made since after the mission was planned allowed the team to downlink data at times they previously didn't expect to be able to, albeit at lower telemetry rates. They therefore decided to collect just one tile's worth of data (the instrument has four detector tiles) at a two-hour rate, and happened to capture a CME during that time.

Space weather

CMEs are an important part of 'space weather.' The particles spark aurorae on planets with atmospheres, but can cause malfunctions in some technology and can also be harmful to unprotected astronauts. It is therefore important to understand CMEs, and be able to track their progress as they propagate through the Solar System.

Studying CMEs is just one aspect of Solar Orbiter's mission. The spacecraft will also return unprecedented close-up observations of the Sun and from high solar latitudes, providing the first images of the uncharted polar regions of the Sun. Together with solar wind and magnetic field measurements in the vicinity of the spacecraft, the mission will provide new insight into how our parent star works in terms of the 11-year solar cycle, and how we can better predict periods of stormy space weather.